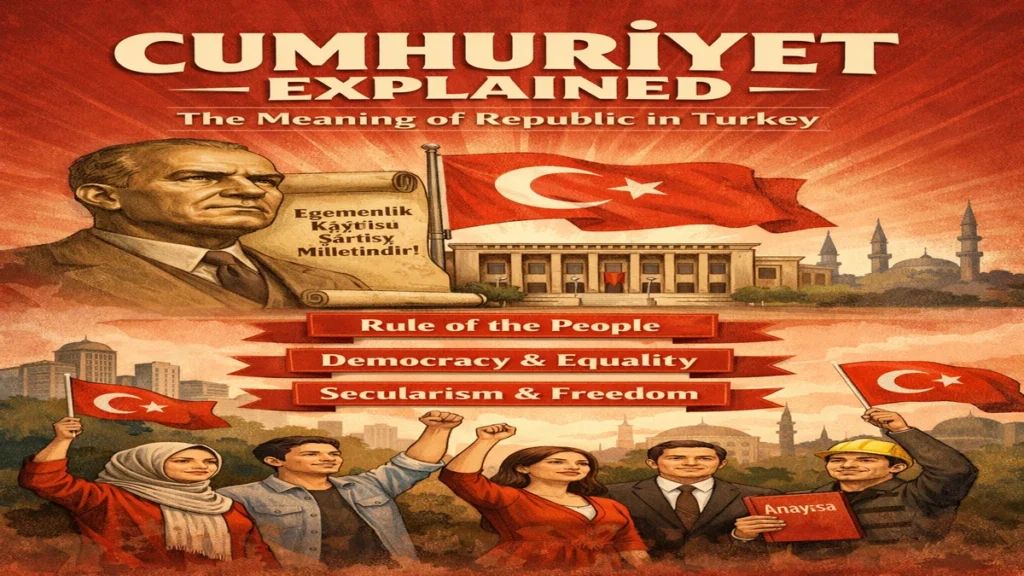

The term “cumhuritey” most commonly understood as a misspelling or phonetic variation of the Turkish word cumhuriyet points directly to one of the most consequential ideas in Turkey’s modern history: the republic. For readers seeking clarity, the intent is straightforward within the first 100 words: cumhuriyet refers to the republican system established in Turkey in 1923, replacing the Ottoman monarchy and redefining sovereignty as belonging to the people. Whether encountered as a typo, colloquial usage, or digital-era variant, “cumhuritey” inevitably leads back to the political philosophy, institutional structures, and cultural debates surrounding republicanism in Turkey.

More than a constitutional term, cumhuriyet has become a symbolic anchor in Turkish public life. It appears in political speeches, school curricula, national holidays, street names, and the title of one of Turkey’s most influential newspapers, Cumhuriyet, founded in 1924. Over a century later, the word carries layered meanings—statehood, secularism, citizenship, press freedom, and contested visions of democracy. Its endurance also reflects tension: between tradition and reform, central authority and popular sovereignty, and competing interpretations of what the republic should represent in the 21st century.

This article examines “cumhuritey” as an entry point into the broader story of Turkish republicanism its historical foundations, institutional expression, media legacy, and ongoing political debates showing how a single word continues to shape national identity and civic struggle.

Linguistic Roots and Conceptual Meaning

The word cumhuriyet derives from the Arabic jumhūr, meaning “the public” or “the people,” combined with a suffix denoting a system of governance. In Turkish usage, it translates directly to “republic,” emphasizing rule by the people rather than by a monarch. Linguistically, variations such as “cumhuritey” often emerge in digital contexts, reflecting phonetic spelling, autocorrect errors, or informal transliteration rather than a distinct concept.

Conceptually, cumhuriyet represents a break from dynastic rule and an assertion of collective political agency. In Turkey, the term is inseparable from the reforms introduced by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, who envisioned a secular, modern state grounded in citizenship rather than religious or imperial authority. Language reform itself was part of this republican project, as Ottoman Turkish gave way to a standardized Turkish alphabet in 1928, reinforcing accessibility and civic participation.

Thus, even when encountered in altered form, “cumhuritey” gestures toward a dense historical and ideological legacy, rooted in the transformation of language, governance, and identity.

The Birth of the Turkish Republic

The proclamation of the Turkish Republic on October 29, 1923, marked a definitive end to the Ottoman Empire and the establishment of a new political order. Emerging from the aftermath of World War I and the Turkish War of Independence, the republic was founded on principles of national sovereignty, secularism, and legal equality. Atatürk’s leadership framed cumhuriyet as both a system of governance and a civilizational shift.

Key reforms followed rapidly: the abolition of the sultanate and caliphate, the adoption of civil law codes modeled on European systems, expanded education, and the enfranchisement of women. These reforms were justified as necessary to align Turkey with contemporary notions of republican governance and modernity. The republic became not merely a political structure but a moral and cultural project.

From its inception, however, the Turkish Republic contained inherent tensions between centralized authority and democratic participation, between secularism and religious expression. These tensions continue to define debates over what cumhuriyet means in practice.

Cumhuriyet as a Political Ideal

Republicanism in Turkey has never been a static doctrine. Throughout the 20th century, different political movements claimed the mantle of cumhuriyet to advance divergent agendas. For some, it symbolized strict secularism and state-led modernization; for others, it represented popular sovereignty and democratic pluralism. Military interventions in politics were repeatedly justified as efforts to “protect the republic,” illustrating how the term could be mobilized both to defend and to limit democratic processes.

In contemporary discourse, cumhuriyet remains central to constitutional debates, judicial independence, and electoral legitimacy. Opposition movements often frame their critiques as defenses of republican values, while governing parties reinterpret the concept to align with evolving political priorities. This semantic flexibility has ensured the term’s persistence but also intensified disputes over its true meaning.

Political scientist Ergun Özbudun has observed that Turkey’s republican framework has oscillated between liberal and authoritarian interpretations, reflecting unresolved questions about sovereignty and representation. Such analyses underscore why even minor linguistic variants like “cumhuritey” resonate within broader ideological struggles.

The Newspaper Cumhuriyet and Press Freedom

One of the most enduring institutional embodiments of republican ideals is Cumhuriyet, a daily newspaper founded in 1924. Established to support the new republic’s reforms, the paper evolved into a prominent voice for secularism, investigative journalism, and opposition politics. Over decades, it chronicled Turkey’s political transformations while often facing censorship, legal pressure, and arrests of its journalists.

The newspaper’s history mirrors the broader fate of republican ideals in Turkey. Periods of relative press freedom alternated with crackdowns, particularly during times of political polarization. International organizations have frequently cited cases involving Cumhuriyet journalists as indicators of press freedom conditions in Turkey.

Media scholar Erol Önderoğlu notes that Cumhuriyet functions as both a journalistic institution and a symbolic battleground, where debates over republican values, free expression, and state authority are publicly contested.

Republicanism in Education and Public Life

The concept of cumhuriyet is deeply embedded in Turkey’s educational system and civic rituals. National holidays, particularly Republic Day on October 29, commemorate the founding moment through parades, speeches, and public ceremonies. School curricula emphasize republican principles, presenting them as foundational to citizenship and national identity.

Public spaces—statues, squares, and institutions—frequently bear the name Cumhuriyet, reinforcing its visibility in everyday life. Yet this omnipresence also invites reinterpretation. Younger generations, shaped by digital media and globalized culture, often engage with republican ideals differently than earlier cohorts, questioning their relevance or reimagining them through contemporary democratic norms.

Sociologists argue that this generational shift does not signal rejection but transformation, as the republic’s meaning adapts to new social realities while retaining its symbolic core.

Comparative Perspectives on Republican Models

| Country | Republic Founded | Core Republican Principle |

|---|---|---|

| Turkey | 1923 | Secular national sovereignty |

| France | 1792 | Popular sovereignty and laïcité |

| United States | 1776 | Constitutional representation |

| Italy | 1946 | Democratic pluralism |

| Dimension | Turkish Republic | Classical Republican Model |

|---|---|---|

| Secularism | Constitutionally embedded | Varies by state |

| State Role | Strong central authority | Mixed |

| Media Tradition | Politically contested | Institutionally protected |

Expert Perspectives

Historian Erik Zürcher argues that the Turkish Republic represents one of the most radical nation-building projects of the 20th century, redefining identity through law and language.

Political theorist Feroz Ahmad notes that republicanism in Turkey has always been a “negotiated ideal,” reshaped by power struggles and social change.

Media analyst Yaman Akdeniz emphasizes that debates over cumhuriyet today are inseparable from questions of digital rights and press freedom.

Takeaways

- “Cumhuritey” refers back to the Turkish concept of cumhuriyet, or republic

- The term symbolizes popular sovereignty and modern statehood

- Its meaning has evolved through political conflict and reform

- Media institutions like Cumhuriyet embody republican debates

- Education and public rituals sustain republican identity

- Contemporary interpretations remain contested and dynamic

Conclusion

The persistence of “cumhuritey,” even as a linguistic variation, underscores the enduring power of cumhuriyet in Turkey’s political and cultural life. More than a constitutional label, it represents an ongoing conversation about authority, citizenship, and freedom. From its revolutionary founding to present-day debates over democracy and media, the republic remains both an achievement and a question—one that continues to shape Turkey’s future. Understanding the word is therefore inseparable from understanding the nation itself.

FAQs

What does cumhuritey mean?

It is a variant or misspelling of cumhuriyet, meaning “republic” in Turkish.

When was the Turkish Republic founded?

The Republic of Turkey was proclaimed on October 29, 1923.

Is Cumhuriyet also a newspaper?

Yes, Cumhuriyet is a major Turkish newspaper founded in 1924.

Why is cumhuriyet controversial?

Different political groups interpret republican values differently.

How is the republic celebrated in Turkey?

Primarily through Republic Day and civic ceremonies.

REFERENCES

- Zürcher, E. J. (2004). Turkey: A modern history. I.B. Tauris.

- Ahmad, F. (2003). The making of modern Turkey. Routledge.

- Önderoğlu, E. (2019). Press freedom and republican values in Turkey. Index on Censorship. https://journals.sagepub.com/home/idx

- Akdeniz, Y. (2020). Freedom of expression in Turkey. Human Rights Law Review. https://academic.oup.com/hrlr

- Republic of Turkey. (n.d.). History of the Republic. https://www.turkiye.gov.tr